by Peter Nelson

Back in the mid-sixties, I lived just outside of Anchorage for a couple of years, and one of our favorite excursions was to drive down to Portage Glacier, about 50 miles southeast of the city, down the Seward Highway.

One of the arms of the glacier is accessible from the road, and a stream coming down from the mountains had, over the centuries, hollowed out a channel under the base of that glacial arm, and it was just big enough to crawl into.

Once you were inside, it was big enough to stand up and explore. I’m so sorry to have nothing but these sadly faded photographs to show how otherworldly lovely it was inside that magical realm. I’ve never seen blues anywhere like I saw in those ice caves. The immense layers of ice filter out all the other colors from the sunlight that manages to penetrate down inside there. We wandered around inside there for hours, in spite of the cold and the wet. It was just ethereal.

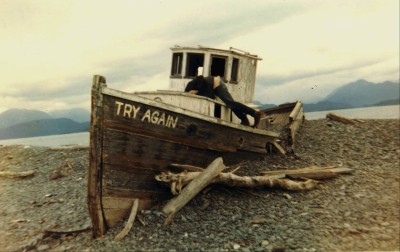

Hang a right off the Seward Highway, and eventually, you’ll wind up in Homer. Here the road ends in a fishing village. Out on the spit, appropriately named Land’s End, I found this wonderful old derelict boat and decided to search it for salvage treasure! What a great name for the old girl, eh?

Always wanted to get up into the far North, and got a chance when I was hired by a geophysical prospecting company. Because the northern tundra is such a sensitive environment — it can take 100 years for wildflowers to rejuvenate, for example — all work with equipment must be done in the winter when the land is frozen solid. Our crew worked out of a mobile trailer camp — an office/kitchen, a bathroom/storage facility, a mechanics shop/generator, a large bulldozer, and two bunkhouses. When we were encamped, we split the trailers into two groups, facing each other. The idea was to reduce the icy wind somewhat, but in fact, that layout just channeled it between the two groups, so stepping out of your trailer was FAR worse than jumping out of an airplane! When it was time to move on, the bulldozer just hooked everything up into a single line, and off we went across the frozen waste.

And of course when you’re north of the Arctic Circle in the wintertime, aside from the frosty temperatures, you also have no sun! Zero. Zip. Nada. Never see that glowing disk, that glorious eternal source of warmth and happiness! The best light we ever got was a low sun at midday at the very beginning of the work season.

I was what was affectionately referred to as a “jughead”. [No offense to the delightful character in the Archie comics.] Our noble brotherhood marched along in the dark, in the cold, in the snow, in the wind, and every 50 paces, we stopped, pulled a geophone [also known as a “jug”] out of our pack, pushed it down into the snow and then stepped on it, before striding off again. We did this all day, every day. Not very exciting work, you say? You’re quite right. Extremely unpleasant working conditions, you say? Right again. Nothing to do when you get back to camp, you say? Hey, you got three out of three! No one in his right mind would do this work, you say? Well, this time you’re wrong. After working up there for 3 ½ months, I’d saved so much money that I travelled for 4 YEARS before I needed to work again!

The dangers of working outside in those conditions were very real indeed. It’s an Alaskan state law that workers cannot be required to work outside if the temperature is lower than -40ºF. The key word there is “required”. In fact, our hearty bunch never said “no”. [Incidentally, because of the extreme isolation, we were paid for 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, whether we worked or not. So we got paid just the same when we were lying in our bunks reading comic books and listening to Tammy Whinette (sic) as we did when we were facing that fierce wind.] I remember trudging along one day when it was -78º. Can’t even imagine what the wind chill must have been!

Ever been in a whiteout? That’s an unusual foggy condition when lowering clouds and drifting snow totally destroy all light contrast. The snow beneath your boots, the sky above your parka hood, the light in front of your face and those distant snow drifts a mile away — all are EXACTLY the same color and painted with EXACTLY the same light intensity. No other conditions on this planet are so utterly disorienting.

In a normal environment, your eyes gather light, estimate distance to the ground and other nearby objects, and send this information to your brain. Your brain then very kindly passes these vital facts down to your feet, so they have a pretty good idea of where the ground is! Not true in a whiteout. There is no color. Everything visible has been bleached out, completely drained of contrast. There is no longer any distance whatsoever, but also nothing appears close to you. All sense of proportion is gone. This sounds like a minor inconvenience, and provided you know exactly where you are and what the snow is like beneath your feet, it is relatively minor. But you have absolutely no idea if you are about to step off a cliff or into a yawning chasm! Even a two-foot drop will seriously shake your spine because it’s so totally unexpected.